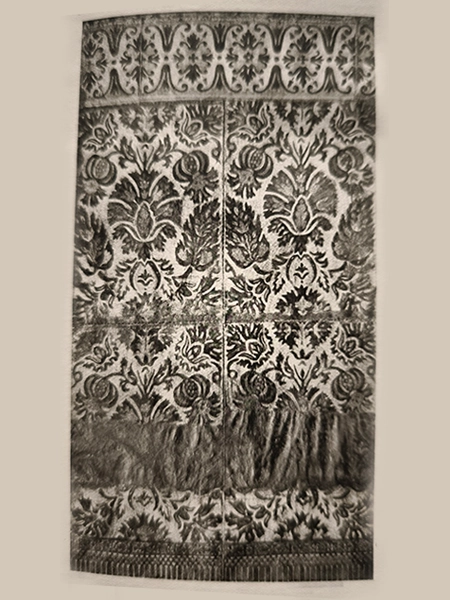

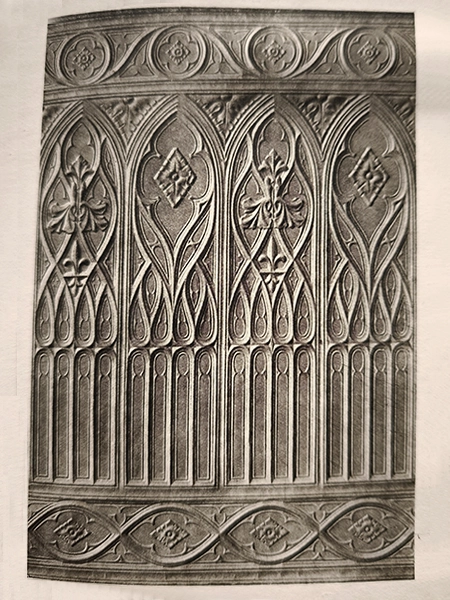

Frederick Edward Walton and his brother, William, who in around 1860 invented the process for oxidizing linseed oil to produce an alternative form of rubber and originated the linoleum floor-cloth industry, described in the booklet ‘The infancy and development of linoleum floor-cloth’ [1925]. He coined the word ‘linoleum’ – ‘linum’ [flax] and ‘oleum’ [oil] and in April 1863 took out a patent on the floor-covering. In the year 1877 it occurred to the inventive mind of Frederick Walton that the material was capable of development in another and totally distinct way. Instead of applying it to floors he would, with some variation in its manufacture, apply it to walls, but with a modeled surface in relief in lieu of the printed coloured surfaces of the floor covering. The resulting product was Linoleum Muralis which was subsequently re-named Lincrusta Walton; ‘Lin’ for ‘Linium’ (flax) and ‘Crusta’ (relief) one of the chief ingredients of Lincrusta being solidified linseed oil, and the inventor’s name being added to prevent other firms using the same title.

For flexibility and resiliency Lincrusta Walton is quite unequalled. Earlier productions were sufficiently strong and stiff enough to hold a wall up if there were any structural weakness. After a very few years’ experience, and thanks to valuable comments and practical suggestions from some of the most prominent decorators who showed a keen interest in the development of the article, the old heavy canvas backing was discontinued in 1887 and superseded by a light waterproof paper. In due course the wall paper merchants realized its value and commenced to insert mounted samples and illustrations in their new pattern books.

Cameoid was the invention of D. M. Sutherland, the manager at Sunbury, and was originated in 1888 as an attempt to meet the competition with and demand for lightweight relief materials. The directors however, were unwilling to market an article which might compete with Lincrusta proper, and it was not until 1898 that they decided to produce Cameoid. It is interesting to note that the discoverer of Anaglypta by T. J. Palmer, who left the Lincrusta Co. in 1886, where he was London showroom manager and because of this same reluctance to admit alternatives to the original. Production of Cameiod ceased in around the year of 1915.

The year 1902 marked a further step in the development of Lincrusta with the introduction of glazed tile patterns which were instantly recognized as being a perfectly sanitary and hygienic decoration. Hospitals and public institutions were quick to appreciate the value of the new line, produced in a variety of colours with a permanent glaze, showing no perceptible joint.

Apart from its use for general decorative purposes, Lincrusta Walton was extensively used in ships, yachts, railway carriages, tramcars and motor cars. For shop-fronts and fascias it proved very effective and durable, being particularly adaptable for exterior decoration through its imperviousness to the weather if well painted or varnished after application. It is the only relief material which from the nature of its composition is not affected by the white ant, and, is therefore extremely suitable for tropical countries.

The introduction of Lincrusta Wainscot in 1912 (first used for panelling the Masonic Temple at Chester) opened up again an entirely new field. A form of oak dado had been previously tried in 1884, but this new innovation was an effective replica of real oak, capable of being stained to any colour and then polished with any ordinary wood polish. It could be applied at a fraction of the cost of real wood with precisely the same effect.

In 1918 the manufacture of Lincrusta was transferred to Darwen from where it was originally manufactured at Sunbury-on-Thames. As an alternative to oak panelling the company then brought out an excellent imitation mahogany, following this up with a range of plain leathers, which were an extremely good reproduction of actual skins. Lincrusta silks, another revival of a previously unsuccessful experiment (1885), had also been introduced and obtained a firm hold on the market at the second attempt.

Due to the Second World War, a number of pattern rollers were lost being seconded for the production of armaments, banishing them to the history books and reducing the range.